During normal times, more than 20,000 people would pass by Brian Baisi’s Italian deli every lunch hour—a steady stream of engineers, geologists, accountants and other hungry workers in downtown Calgary, the heart of Canada’s oil industry. But these are no longer normal times. Today, nearly 30 percent of all the offices in the city’s densely-packed business district sit empty. And in front of the deli, the usual midday flood has been reduced to a trickle. “We went from an extremely viable, busy restaurant to zero,” Baisi told local news last year.

It’s a reflection of the difficulties faced by oil and gas since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Unlike previous downturns, though, the industry that emerges from this one will not look the same as before. “Oil and gas is used to a severe business cycle, where prices can go down from $100 to $25,” says Richard Marshall, Nakisa’s Head of Oil & Gas Industry Practice. “They’re used to contracting and expanding their business. But this is a little different.”

A seismic shift

Oil and gas is undergoing some of the biggest changes it has seen since the industry emerged just over a century ago. At the beginning of last year, the sector was still recovering from the 2014 crash in oil prices, when an abundance of shale oil being extracted in the United States sparked a global price war. And it was just beginning to negotiate the path toward international climate goals, which demand cleaner, lower emission forms of energy—a process known in the industry as the energy transition. Then the pandemic hit, sending demand for oil tumbling down 30 percent, with prices along with it.

The industry responded by restructuring. Last fall, after losing more than two thirds of their respective share values, two of Canada’s biggest oil companies—Cenovus and Husky—announced a merger. Husky CEO Rob Peabody said the move would save each company more than a billion dollars, allowing them “to make better returns in a tougher environment.” But those cost savings come at the cost of layoffs, meaning a complicated reorganization is in order.

Many other companies in the industry have been taking a similar path: merging with or acquiring other companies, or otherwise trimming their workforce in order to stay competitive in lean times. But the changes aren’t just a response to the pandemic. Countries around the world are introducing more ambitious measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, with the United States pledging in April 2021 to reduce emissions up to 52 percent by 2030. Such policies mean the oil and gas industry will never return exactly to what it was before, prompting big changes in the workforce as it adapts to new realities.

BP recently made headlines by gutting its exploration division, reducing a team of 700 geologists, engineers and scientists to less than 100. That’s just a small part of a much larger reorganization that will see the petroleum giant reduce its global workforce by 15 percent. It’s all part of a goal to reduce oil production by one million barrels per day while growing renewable energy output 20-fold.

BP is far from alone in its ambitions. Analysts at Deloitte have projected that 70 percent of jobs lost during COVID-19 will not return by the end of 2021. In Canada, where the number of oil and gas jobs soared by 71 percent from 2001 to 2014, economists expect all of those gains—and more—to be wiped out in the coming years, with up to three quarters of the workforce eliminated.

That’s a remarkable contraction, made all the more remarkable considering that the smaller workforce that remains will need to handle the industry's transition to cleaner energy. “The sector is already quite, quite thin in terms of the number of people working in the industry,” says Carol Howes, Vice President of human resource consultancy PetroLMI. “As a result of that, we only have so much we can cut, so many places we can cut in terms of employment.” Oil and gas companies need to be ready for the enormous challenge of finding out how to reorganize their workforces—not just for efficiency, but for survival.

The human impact

From a human resources perspective, oil and gas is a particularly complicated industry. “They have to operate where the oil and gas is, where the actual resources come out, and they also have to distribute it everywhere that is needed,” says Marshall. A vertically integrated oil and gas company will be involved in everything from exploration to production to distribution, with workers in situations as diverse as corporate offices, geological field sites, refineries and retail employees taking cash from customers.

Further complicating matters is the scope and diversity of the workforce. Before the pandemic, less than one percent of oil and gas workers were able to work flexibly or remotely, according to Deloitte. “You’ve got a mixture of full-time employees and contractors who have to be where the oil is, and it can be in all different parts of the world,” says Marshall. “When you think about COVID and travel restrictions, different pandemic restrictions and responses, that adds complexity.”

The current economic situation means companies need to do all of that while making do with less. In the case of the Husky-Cenovus merger, for example, the two companies will need to understand which parts of their operations are made redundant by the merger and make changes accordingly. Then they will need to understand which companies’ assets meet the other’s needs. Cenovus was focused entirely on extraction from the Alberta oil sands until it acquired ConocoPhillips in 2017 and gained a foothold in refining and distribution. But it has no retail business, and no experience in the Asia-Pacific market, unlike Husky, which operates gas stations and is heavily involved in China and Indonesia.

“They're going to have to emphasize the asset they bring from Husky—[and] the people that can help them manage that asset,” says Rafi Tahmazian, an analyst with Canoe Financial.

Planning for the future

Visualizing organizational change will be crucial in the coming years as the oil and gas industry recovers from COVID-19 and embarks on the path to energy transition. As Deloitte noted in a recent report on the future of work in oil and gas, the key challenge is to create more efficient operations while also pivoting to new forms of energy—or as Deloitte put it, managing “big layoffs amid the great crew change.”

The report notes that, “instead of developing a piecemeal digital and automation road map for a business unit, organizations need to redraft the operational vision and ascertain the future ways of working for the entire organization.”

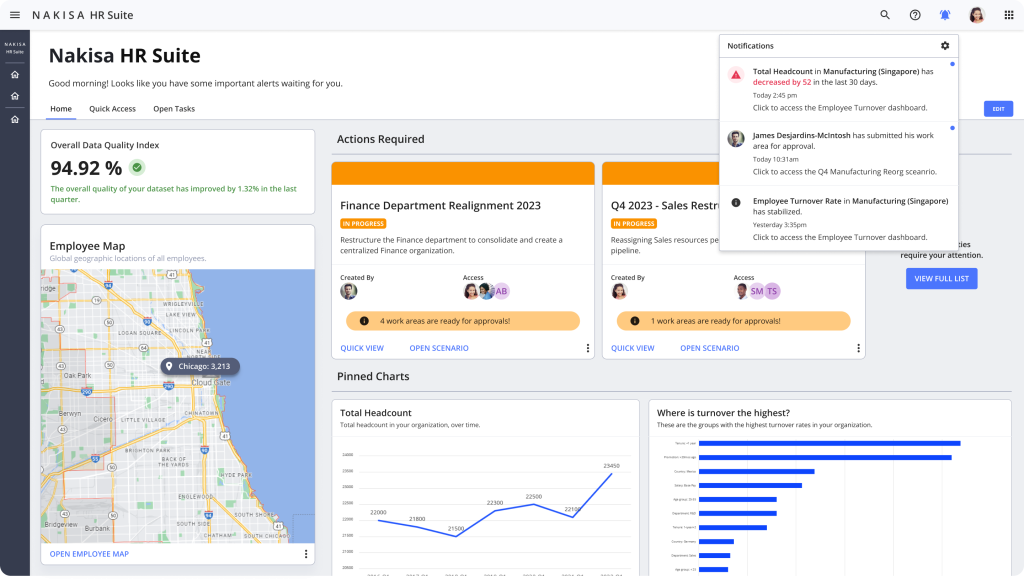

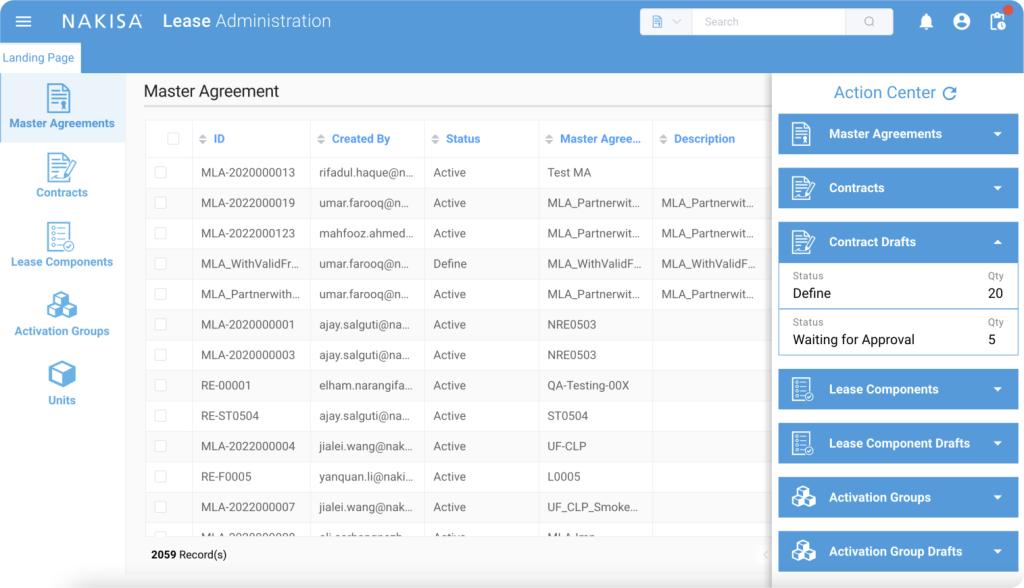

Marshall says this is where many companies risk stumbling as they try to find a path forward. “Is there a way to visualize all of that change easily? That’s not usually the case,” he says. “Your traditional people management systems focus on the key things about onboarding employees, making sure they get paid and have the requisite training and skills—that type of stuff. But being able to easily picture where all those people are globally, against your assessment of different territories and geographies, their risk levels and responses, that’s not easily seen in many systems.”

Nakisa’s Hanelly solution is an important tool in a situation like that. “With Hanelly you can see it in a different way,” says Marshall. “You can do a side-by-side and start to understand the risks and opportunities and formulate a response.”